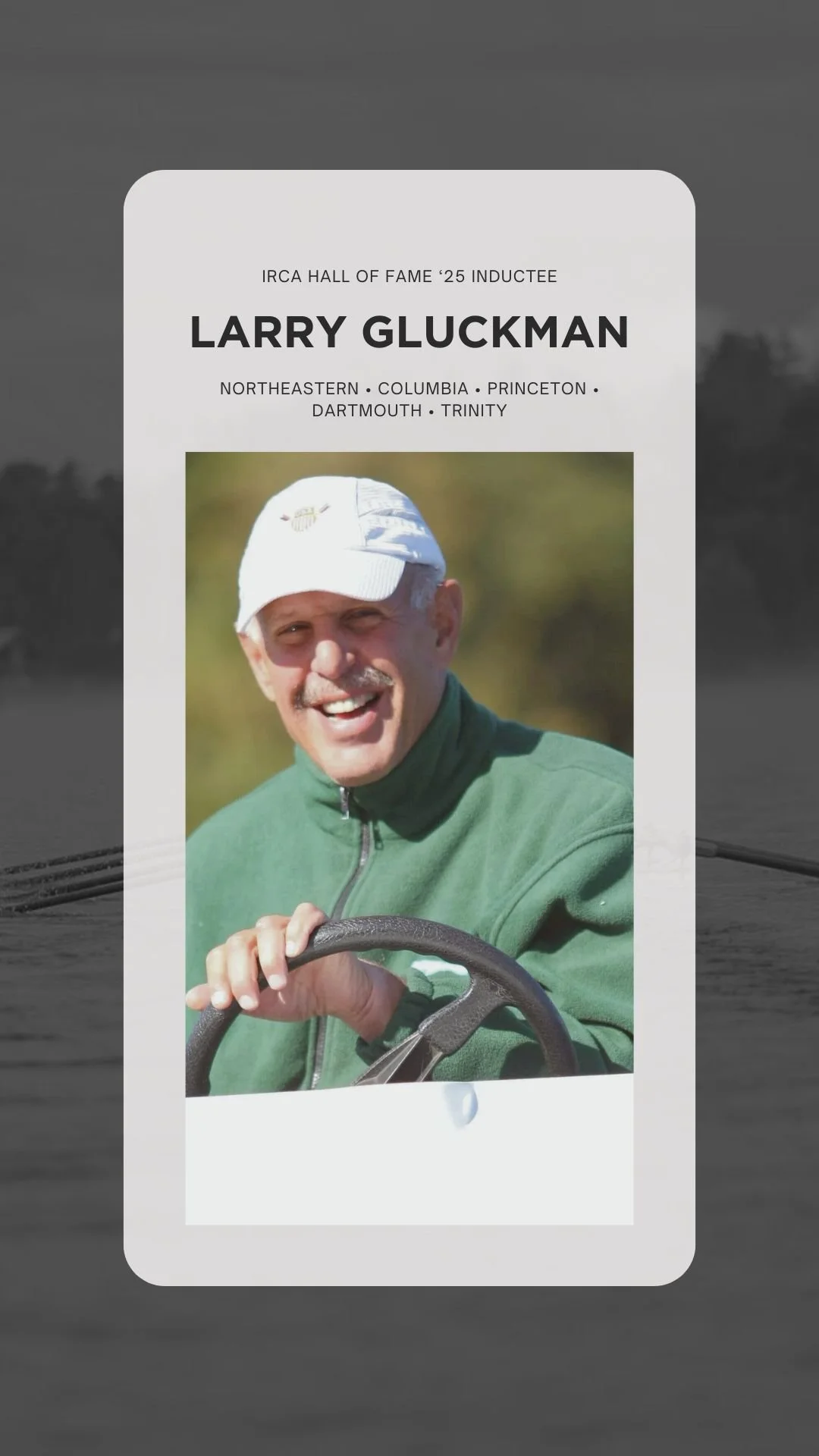

Announcing the 2025 IRCA Hall of Fame Inductees

Written by Kevin MacDermott, Trinity College

As Head Coach from 2003-2009, Larry Gluckman led Trinity College’s rapid ascension to elite status among the nation’s small college rowing programs, guiding his varsity crews to a 42-4 record in dual races during his tenure. Gluckman coached crews that won two ECAC national invitational gold medals and one ECAC silver medal, three gold medals in the Collegiate 8+ at the Head of the Charles Regatta, four New England Rowing Championship titles and four NESCAC Championship crowns. The Joy of Sculling Collegiate Coach of the Year in 2006 and 2007, Gluckman gained international renown for the College when Trinity’s top crew won the Temple Challenge Cup at the Henley Royal Regatta in 2005 and reached the final in the same event in 2008.

Before his success at the Division 3 level, Larry had a long and successful career at the Division 1 level, coaching crews at Columbia, Northeastern, Princeton, and Dartmouth. He helped guide each program to success, highlighted by Eastern Sprints and IRA medals for his Northeastern crews in 1978 and 1979 and a historic IRA victory by his Princeton varsity crew in 1985. Following this stretch of coaching, Larry spent twelve years working for Concept2, helping innovate new products and serving as a primary customer service resource for the company.

Larry kept trying to retire but wasn’t very successful at hanging up his megaphone and stroke watch. After retiring from Trinty, he founded and led the Craftsbury Small Boat Training Center which has grown into the Craftsbury Green Racing Project. He guided numerous crews and individuals to success at the U-23 and senior national team level. Larry loved his family, enthusiastically rooted for the underdog, always had a cold Old Milwaukee in the cooler, and cherished teaching people anything and everything he could about rowing.

Written by Bill Randall, US Coast Guard Academy

Anyone who has ever met Bill Stowe has a “Stowe Story.” I have head hundreds. Some are more repeatable than others. I was fortunate enough to first meet him while learning to scull at Blood Street Sculls and, for reasons I am not sure I understand to this day, I followed him to CGA.

In 1971, Bill was the right coach at the right time at the Coast Guard Academy. He was larger than life. He was an Olympic gold medalist and one of the best rowers of his generation. He was already an established coach who came to CGA from Columbia, not in small part because of the urging of Fred Emerson, who worked with Otto Graham, the Athletic Director at CGA at the time, to fund and start a rowing program at CGA.

My first Stowe story – it was early February 1971 and there was an announcement that CGA would be starting a rowing program. When Stowe arrived at the meeting there were over thirty guys waiting, more than he could deal with. He decided the way he would reduce the number of perspective rowers was to give a fire and brimstone speech about how hard rowing was, the misery of the cold wet rows that awaited them on the Thames, the early morning (I recall that we had to be off the water and at formation by 0625), etc.

Not one cadet left the meeting.

But, as Stowe was leaving two new cadets came up to him, said they had heard part of the speech and wanted to know if they could join too. The first team literally broke ice to start rowing in February of 1971. I have the pictures of wooden boats launched from Red Top, Harvard’s training facility on the Thames, with ice clearly visible – it was definitely not “safety first”, but it was okay, they all knew how to swim. After those first rows, they traveled to Florida in March for spring break, won their first race, and the program was off and running.

In the second year of the program CGA shocked almost everyone, including themselves, by winning the Dad Vails. Over the next 10 years CGA won eight Dad Vail Championships including six in a row. The victories in the 1V were complemented by three victories by the varsity lightweights, numerous JV, and freshman victories, and I believe nine team trophies in Philadelphia. Further, under Stowe’s tutelage CGA raced some of the best D1 teams in the country (I had a racing shirt that said Beat Navy, and they did – I think it was in 1977 and 1978), made the finals in the varsity eight race at the IRAs in 1975, won the straight 4 and coxed four events at the IRAs, and rowed in races across the US, in Egypt, and at the Royal Henley Regatta in England.

In short, he oversaw the most successful period CGA rowing has ever had. He led the program from 1971 until 1985 and he left a legacy including two rowers who went on to race for the US National team, rowers that went on to be CG heroes, several successful rowing coaches including Steve Hargis (CGA ’80), Bill Zack, the CEO of Vespoli, and me.

I never quite figured out his magic, he kept the stroke simple, he believed in HARD STROKES (what we would now call HIIT – except we did it several times a week), he made the rowers believe, and with that believe came success. I am honored to let you know a bit about Stowe and am proud to represent him for this award.

Written by Greg Hughes, Princeton University

Gordon Sikes is one of the most foundational individuals in the history of rowing at Princeton University and one of the founders of collegiate lightweight men’s rowing. Afflicted with polio at the age of 3, Sikes would spend the rest of his life needing the aid of braces and crutches, something that hardly slowed him in any way.

Sikes became a coxswain as a student at Princeton before graduating with the Class of 1916. The highlight of his undergraduate career came as a senior against Harvard, when Princeton and the Crimson both crossed the line recorded in the exact same time of 9:12.5 before the Tigers were declared the winner by “the width of a butterfly’s wing,” according to the race’s judge Albert Noyes, who would become England’s Poet Laureate.

His bout with polio prevented him from being a frontline soldier after graduation, but he still sailed across the Atlantic and spent the rest of World War I in Paris, where he served in a supporting role for the troops. When he came back to the United States, he began his coaching career as a volunteer with the Tigers.

At the time, there was only one varsity program. Lightweight rowing was introduced nationally in 1919 by Penn coach Joseph Wright, for whom the trophy for the lightweight men’s national champion is named to this day. Princeton, with Sikes as its volunteer coach, created a lightweight crew and competed in one lightweight race in both 1920 and 1921 before rowing a fuller schedule in 1922.

He’d coach the lightweights from 1922-31 before moving to the heavyweights from 1932-37. He became Princeton’s first coach to take a team to Henley when the lightweights traveled there in 1930 (he’d return with them in 1933 and 1934 as well), and he also won two Wright Cups as national champion (in 1926 and 1930).

He’d come back again to the lightweight program in 1943, 1946, and 1947, and he’d remain a huge supporter of the team until his death on Dec. 27, 1982, at the age of 86.

The Gordon Sikes Medal was created in 1958 and has been awarded to a senior lightweight rower at Princeton each year since. The Shea Rowing Center has a meeting space named in his honor. He also spent 45 years as a full-time Princeton employee, mostly as the director of the Placement Bureau, which today is called Career Services. When he finally left Princeton, no other person had ever worked at the University longer, in any capacity.

Written by Colin Farrell, University of Pennsylvania

Joseph Walter Harris Wright was a Canadian Olympic rower and coach, as well as one of the key figures who helped bring lightweight rowing as a collegiate sport to the United States. Born in 1864 in Villanova, Ontario, Wright got his start in rowing as a teenager at the Toronto Rowing Club in the mid-1880’s. As a rowing competitor and coach, Wright had more than a 130 titles to his credit in numerous rowing classes, including taking the U.S. National Fours and Pairs titles in 1895. He competed in the 1904 Summer Olympics and was a member of the Canadian men’s eight which won the silver medal. Wright was also the first Canadian to ever win a heat of the British Henley’s prestigious Diamond Sculls race.

He retired from competition at 42 years of age in 1906. He then devoted his time to coaching at the Argonaut Rowing Club in Canada. He coached the legendary crews of Geoffrey Barron Taylor, helping them win the Royal Canadian Henley Regatta five times. He also coached Taylor’s Argonaut eights crews, representing Canada at the 1908 Summer Olympics, winning the bronze medal, and again he coached at the 1912 Summer Olympics.

Wright was then hired in 1916 to coach at the University of Pennsylvania. Wright, who had seen the popularity of lightweight rowing grow after its introduction to the Canadian Henley in 1906, advocated for its adoption at U.S. colleges. The first intercollegiate lightweight contest, set between Penn and Yale for May 12th, 1917, was cancelled by the onset of WWI. Following the end of the war, on May 31st, 1919, the first event on the program of the American Rowing Association - “Special Eight-Oared Shells (150lb Crews)” featuring Navy and Penn - marked the beginning of intercollegiate lightweight rowing in the US. Navy and Penn’s lightweight crews still race annually for the 1919 trophy.

Since 1938, the trophy awarded to the winner of the IRA lightweight varsity eight race, initially sponsored by the American Rowing Association, and then by the Eastern Association of Rowing Colleges, has been the Joseph Wright Trophy. Wright’s eldest son, George F. Wright, won a bronze medal at the 1908 Summer Olympics and his younger son Joseph Wright Jr. won a silver medal in the double sculls competition at the 1928 Summer Olympics. Joseph Wright died at his daughter’s home in Toronto on October 18th, 1950, and was buried at St. James Cemetery. Two months after his death, Wright was selected by the Canadian Press as the greatest oarsmen of the half-century.